ARTWORK ANALYSIS

Henri Dauman or the photograph of an imaginary community

Former General Curator of the Nicephore Niepce Museum in Chalon sur Saone, curator of the Manhattan Darkroom exhibition, Founder of Red Eyes

“The death of a dream is no less sad than death…”

Truman Capote

NEW YORK,

IMAGINARY CAPITAL

For someone who could no longer expect anything from Paris, New York offered a refuge both real and ideal. The former, that trying city, that capital of a devastated world, could not satisfy the ambition of a young man saved from the Holocaust. The American Dream of Henri Dauman, the possibility of his photographic oeuvre, took shape in the city on the banks of the Hudson. There the face of the city and the path of his destiny were joined. Dauman admired the country before ever having observed it. The man barely lingered in other countries and landscapes. If commissions sometimes dragged him far from his city, he always felt that the rules of the game could not have been set elsewhere than alongside the East River. New York, imaginary capital of an always-new world, is a metonymic figure of modernity itself. One does not see its faults, only lapses presented as temporary adjournments to history. Futures not only seem impossible, but are inscribed in each face, at the corner of each street and in each scene captured by the lens. The simulacrum that is New York-- because that is what it is-- rests entirely on the ideal of a social utopia characteristic of the American model. It fuses roles and topography, both objects of resolution and individual abnegation, that it turns into models for others to follow.

Henri Dauman, as an authentic New Yorker—he took up their habits and characteristics—injected into each assignment an element of the particular mythology attached to Ellis Island, to Brooklyn and Manhattan…

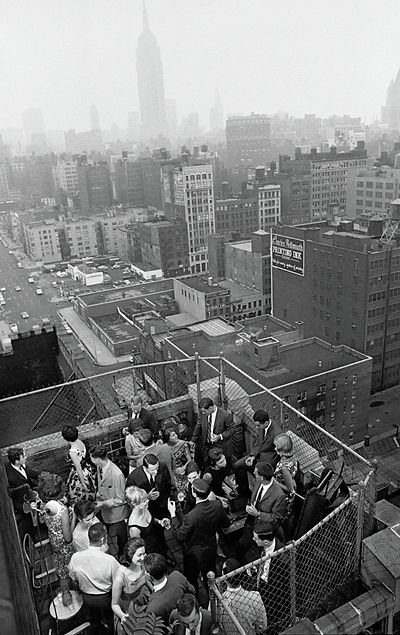

The city has a look. Its geometric character is suitable to the photographer's desire to become one with its tangible, exuberant, and eminently explorable space. Dauman would roam it through and through. The city resembles its architecture, an homage to modernity. As long as that city exists, the era of creators will never pass. The artists here have no debt to the past. Finally emancipated from all historical reference, they renew themselves via the rejection of the European tradition. They accept no pre-established rules, but are solely accompanied by a difficult-to-comprehend morale or by a vague belief in a configuration where anything is possible.

New York plunges with delectation into this paradoxical quest. In the 1960’s and ‘70’s, the City, eager for new paradigms, offers the artist a leading position. Antiestablishment thinking, that visible contradiction that is so striking to the foreign visitor, proves to be an identifying marker of the city. After having welcomed European artists fleeing Nazism, New York took up without inhibitions a research into new figures of modernity. But from now on, these figures will emerge from its own milieu. The cultural supplement of the New York Times abounds with glorious futures, and yet how many of them talentless artists with minor gifts who obtained nothing!

The success of these people and the esteem that one gives them matters little. It suffices surely that they exist. The gallery of New York portraits fits into this daily struggle. Experimenters, conceptualists, handymen for the most part, they only obtained their photographic stipend through direct rivalry with the elements.

This illusion of the American Dream - Henri Dauman's unique message - has perfectly-drawn contours. The photographer's role is to connect the spectator to an entirely fabricated reality. A universe of perceptions, New York must however escape from clichés. As an “objective” confirmation of utopia, the image places the spectator into a truth whose definitions he cannot but accept. Photography validates a vision of a society without rough edges, which presents itself in series of organized and incontestable images. It supports that which the reader cannot consider as a fiction, but only as a precise and unquestionable equivalent of facts and actions. The only dogma of this conquering press resides in an obstinate faith in the objective nature of facts. In 1949, more than 20 million people, reading a print run approaching five million copies, recognize themselves in the pages of Life! It is a conception of America and the world which will be distributed via 8 and a half million copies by 1968, revealing the American ambition to universalize its outlook.

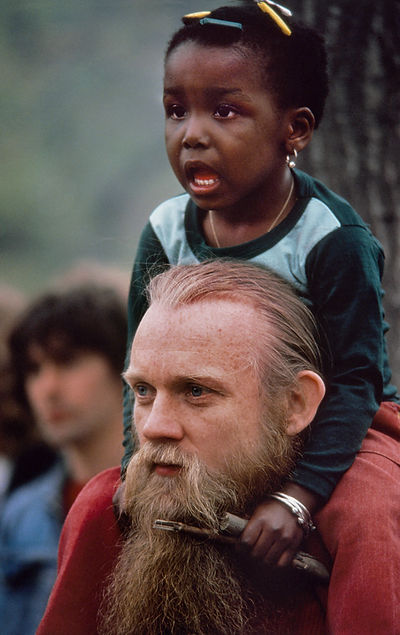

A "COLORED"

MIDDLE CLASS

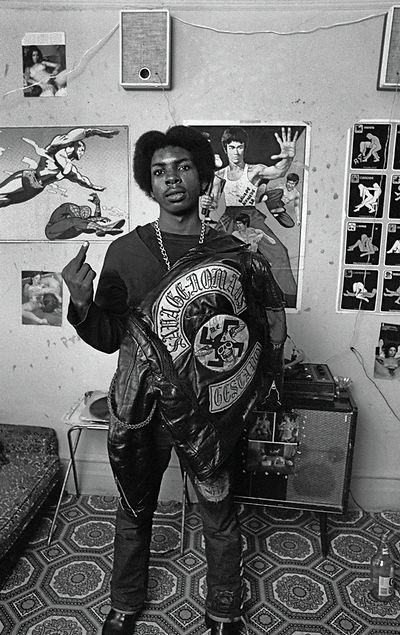

And yet the myth surrounds and exalts the work of the photographer. His photo-essays in Life or his contributions to the New York Times remain faithful to the thinking of Jefferson! The harmony of a society is the consequence of the pragmatism of its entrepreneurs, of its executives and its blue-collar workers. This concern with efficiency in all domains and at every instant is a conviction, a “habitus” one might say, never called into question. Experience and work are the essential elements of truth and the proper functioning of the democracy. This photography smells thoroughly of optimism. It is an optimism anchored in the certitude of the destiny of a people fated to happiness. The photographs of Henri Dauman present ethnic groups previously rejected but from now on invited to rejoin the society of consumers. Blacks and Hispanics should participate in the extension of the domain of commerce. The fight for civil rights, a “humanist” necessity, has no other function but to enlarge the base of interior consumption. It participates in the constitution of a “colored” middle class, attached to American democracy, to its material advantages and its cultural values.

The role of press photographer consists in signaling the obstacles encountered in the course of the quest for progress inscribed in history. Racial segregation, economic disparities, claims of all sorts appear therefore in a kind of apologetic tale, as a whole, made of successive and regular “victories” against these “accidents” or these “anachronisms.” New York and its press have only one problem—the rest of the United States! Wallace really has bad manners and Dick Daley is a provocateur of bad taste! As for its intellectuals, one must chose the acceptable ones. In the ‘60s the New York Times has a weakness for Einstein when he harasses Bertrand Russel…

But this method has its limits. That which the 1950s had led one to believe failed. And all the color photographs in the world could not hold back the wave of protests of the 1960s. The tight link that one would see between generalized consummation, entertainment and democracy, which supported peaceful relations between communities, no longer functioned. The Vietnam War and the conscription of the children of white middle class families put at risk the “Republic of consumers.” A nascent feminism contested the role females were expected to play in businesses. To be sure, the marketplace reigned supreme in the entire North American continent, but this “materialist nationalism” entered into a crisis: just as with the subjection to acquisition, this teleology was derived from Protestantism.

The American press knew how to keep the malaise at a distance. Its trademark is to adapt the reader to a reality that’s under control and all in all acceptable. In an original format, Life evolved towards concise, polished layouts that associated text and image intimately. From now on readers are no longer considered to be looking for knowledge. In the midst of a “cold war,” destabilized by the crisis of traditional values, one imagines them in need of security, wishing to exhibit their membership in the community.

THE MAGAZINE CELEBRATES MORE THAN IT INFORMS.

The editorials, the texts and the captions weave from issue to issue a discourse of authority, with highlighted moments livened up by color. In this sense, the photojournalist is not the spectator he claims to be. He participates in the stagecraft of a world preoccupied only with its preservation and its representation as spectacle. Every journalist is a dramaturge. It’s for this reason that this photographic “writing” is so strongly akin to theatrical or cinematographic technique. New York, the city of Henri Dauman, is laid out in organized stories, in sequence shots, in montages. Neighborhood by neighborhood, social class by social class, floor by floor, one bears witness to carefully constructed episodes.

The conscious objective of the editorial board is constant. The representation of New York is a project. Far from a dream of conquest, contemptuous of vast open spaces, finding the countryside irksome, and thinking of nothing but itself, the metropolis is haunted by nothing. It mocks memory. The documents of Jacob Riis on child workers, the damning reports of Wayne Miller in the Bronx, Gordon Parks’ descriptions of the red neighborhoods of Harlem follow one after the other, and give the illusion of the investigation into truth. Photography, that white knight, doesn’t fear to confront the unjust “natural laws”! Sequences of shots of the poor in squalid surroundings become a moral necessity. The critical document is reserved under an elitist form for the New York Review of Books or the New Yorker. The model offered by these journalistic reports is a palliative interpretive guide, shedding light on upsetting and seemingly illogical events. Life was not far from Fortune.

However, one would be too hasty in equating the editorial line of Life, a magazine, with the New York Times, a daily paper. The Sunday edition of the latter, amply furnished in different sections, intended for a public of great cultural capital, enjoyed an unmatched reputation. The reading of this journal is a choice moment in New York culture. It is an object certifying one’s belonging to the upper classes. In that sense, the portraits and the situations described by Henri Dauman, little theater of vanities and illusions, contribute to differentiating the social classes.

There is nevertheless in the print media of the ‘60’s and ‘70s a continuity in the ever-renewing spectacle of the city's creative energy. The mediated reality is overtaken by the fiction of the true. In this scenario, everyone can and should find the possibility of inscribing themselves into a creative pantheon, a land register of innovation. No matter what part you find yourself in, New York as a place is generous. It is that incessant construction site where the only fear is emptiness. In this country that knows German Philosophy so well, contradiction is at the center of all explanation. From conflict spring forth things, objects. There is nothing more macabre than tradition. But if the imagination of the New Yorker loves so much to flay tradition, it is the better to uphold it. Values are only assured in the protection of respectable principles that the decoy of modernity supports. In fact, there is little appetite for change. The reality of New York is an imaginary projection flaunting itself like a lie, in Guy Debord's terms, in the pages of a magazine or a Sunday supplement. When the new medias reached the point when they could relay this vision better than the press, it deprived photography, now obsolete, of its hegemonic status of representation.

François Cheval

Analysis published in the book

The Manhattan Darkroom